A special Dvar Torah for Rosh Hashanah 2022

by Prof. Zehavit Gross, Dean of Faculty of Education, UNESCO Chair for Values Education, Tolerance & Peace, and Head of the Sal Van Gelder Center for Holocaust Education, Bar-Ilan University, Israel.

One of the most exciting moments in the Rosh Hashanah prayer in my view is the Haftara reading on the first day of Rosh Hashanah which relates the story of Elkanah’s wife Hannah, Samuel’s mother (I Samuel Chapter 1). I feel that this is one of the most dramatic chapters of the Bible. It is also a chapter that I relate to personally, because I too experienced similar challenges and experienced God’s redemption through the birth of my children. It is precisely because of my personal experience and the fact that for many years I prayed to the creator of the universe to save me and give me a child, that I understand Hannah’s story from several different dimensions and perspectives. Yet, one of the troubling questions for many commentators and literary and biblical scholars is how a woman can pray for a son and at the same time make a vow to give him to God. I think that a profound feminist reading of this exciting text will yield a new understanding and consciousness that will explain the meaning of the events and the ostensible paradox that lies in the very special figure of Hannah.

In my opinion, the climax of this story is the coat that Hannah sews for her son after she gives birth to him and weans him and before he goes to worship God in the Tabernacle. The Bible states: “Moreover his mother made him a little coat.” (1 Samuel 2:19)

If I had the courage, I would have sown my son a little coat like the one that Hannah sewed, but I lack that vision and inspiration, and am incapable of comprehending the magnitude of the mission that Hannah took upon herself and passed on to her son. What Hannah sewed for her son is both a kingdom and leadership. By means of the coat, she “marks” him for royalty. According to the commentators, this coat was a status symbol and it accompanied Samuel until his death and after it as well. When Saul tried to convince Samuel to come with him to sacrifice to God after the victory over Amalek, Saul grabbed hold of Samuel’s coat, and when Samuel turned to leave, the coat tore, and this was a sign of tearing the kingdom from Saul: “And Samuel said unto him, The Lord hath rent the kingdom of Israel from thee this day, and hath given it to a neighbor of thine, that is better than thou.” (1 Samuel 15:28)

Even after Samuel’s death, when Saul asked the Witch of Endor to bring up Samuel’s soul, the Witch of Endor saw the ghost of a man wearing a coat over his clothes: “And he said unto her, What form is he of? And she said, An old man cometh up; and he is covered with a mantle. And Saul perceived that it was Samuel, and he stooped with his face to the ground, and bowed himself.” (1 Samuel 28:14)

Through her vow, Hannah a priori perceives pregnancy and childbirth as a national mission. Pregnancy is impersonal and therefore cannot be understood through the ordinary “possessive” categories of motherhood. I recently completed several studies with two MA students and another researcher on the subject of observant and nonobservant Jewish women who give birth to a large number of children. We found that women have children first and foremost as an act of self-fulfillment and emancipation rather than for the sake of society or any other exalted goal. However, in Hannah’s case, contrary to the normal, conventional concept of motherhood, pregnancy is not intended to satisfy a woman’s natural needs, to create continuity for herself or for self-fulfillment.

Hannah, who was a prophetess, perceived Samuel, the son who was lent to her (the meaning of the name Samuel in Hebrew is loan) as a conduit for the realization of more exalted social and spiritual values in order to create a common good for the People of Israel which was divided into tribes. The coat is the profound manifestation of her prophecy of achieving self-fulfillment through her son’s leadership and through the vision and path that she is building for him in the public leadership of the People of Israel, which is gradually taking shape and becoming a reality. The coat helps Hannah and those around her understand the meaning of her mission and direction. It expresses the constructivist process of creating the vision.

The coat is a proactive expression of Hannah’s agency and control over the process and the construction of a kingdom. With Esther, too, it is said, “that Esther put on her royal apparel” (Esther 5:1) and only when she wears royal clothes does she become Queen Esther. Only then does she internalize the magnitude of the mission and the national responsibility that rest on her shoulders. At this point she undergoes a transformation that enables her to go to Achashverosh and fight Haman and his evil plot to annihilate the Jewish People. Wearing royal clothes frees her from her shackles, indicates the way and gives her a mantle of psychological confidence enabling her to carry out her mission.

Jacob the Patriarch also sewed a coat of many colors for Joseph (Genesis 37:3) because he understood in the prophecy that Joseph was destined for a great national mission. Every mother should sew her son a little coat if she wants him to be able to build a kingdom. He will adjust the coat throughout his life to his size and needs and the challenges that he will face. Every mother should give her son the initial push that will put him on the right track. However, she must also know when to let go until she weans him, and this is what Hannah had the wisdom to do.

Only a woman with a female sixth sense is capable of doing such a thing. Throughout the story, Hannah shapes and builds the plot by exercising agency and being proactive. The coat is the epitome of both her and his liberation. When she was barren, she turned to God and referred to herself as a handmaid. And she vowed a vow, and said, O Lord of hosts, if thou wilt indeed look on the affliction of thine handmaid, and remember me, and not forget thine handmaid, but wilt give unto thine handmaid a man child, then I will give him unto the Lord all the days of his life, and there shall no razor come upon his head. (Samuel 1 1:11)

I have seen modern commentaries claiming that Hannah wanted to bind Samuel to her through the use of the coat and that she regretted her decision to dedicate him to the service of God. In my opinion, this is a distorted reading that has no basis in the text and dwarfs Hannah, her rich spiritual world and her agency. What actually happened in this particular canonical biblical text is the exact opposite. As soon as Hannah conceived and gave birth to a son, she was liberated and celebrated this by making the coat and writing a prayer of thanksgiving, Alatz libi baAdonai, which helped her to be liberated. In effect, when Hannah gave birth, she also gave birth to a new Hannah and to a kingdom. She takes Samuel on loan in order to breastfeed him and give him food for the road, but she also weans him, thereby liberating both him and herself.

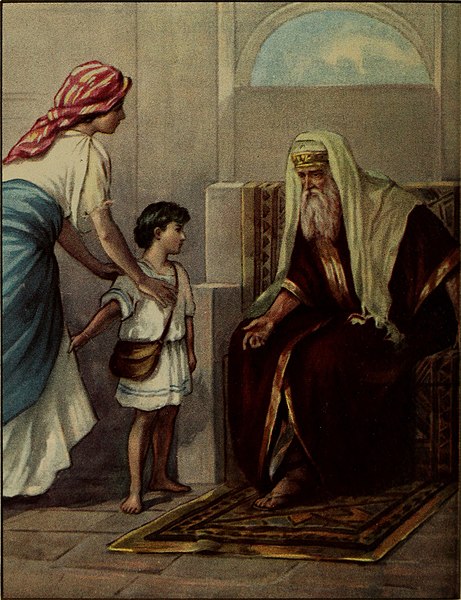

Martin Buber distinguishes two states of connection in relationships between people: between the “I-It relationship”, which is distant, and the “I-Thou relationship”, which is close. When Samuel is born, to some degree he is an object or an “it”, to quote Buber. He is an “it” that she took and nourished. Then, she delivered Samuel to Eli the High Priest once he is weaned, and their relationship is an “I-It relationship”. But when she sewed the coat for him, she seemingly distanced herself from him to realize his mission. However, a deep “I-Thou relationship” is actually created between them, since that coat will accompany him spiritually throughout his entire life. In every single seam that she put in the coat, she invested love and a heartfelt prayer for his success through his mission and the success of the world. Hannah was the ultimate believer. She believed that everything in this world is temporary and is in the hands of the Creator of the Universe, but she also believed that through prayer it is possible to change reality and create a new world. This is why we read this parasha on Rosh Hashanah. Through our prayers, we wish to create and change the world, making it a better place.

Giving the child to do the work of God is a form of emancipation and liberation from a state of absolute helplessness to a state of liberation and absolute control over the situation. This is the construction of leadership out of freedom of choice. It was her vow to give him over to serve God. Nobody forced her. Samuel is the firstborn fruit of Hannah’s loins. Just as the first fruits are brought to the Temple, he is “bound with elastic” and given with great love for his mission of serving God in the Temple. By means of the coat, she sews his confidence and creates warmth and a safe place for him inside it.

When she gave birth to her son by virtue of her vow, she experienced a transformative process of liberation. She liberated herself from the natural maternal possessiveness and sense of ownership that every mother has over her son. She also underwent a healthy psychological process of separation to enable her son to achieve the individuality that would enable him to be ready for his mission.

The feminist psychologist Nancy Chodorow (1978) claimed that, while women build their identity through connection, men build their identity through separation, which they need in order to structure their masculinity and healthy intimacy. The Torah says something in this vein when a person is about to get married “therefore a man shall leave his father and mother and cleave to his wife.” Separation between mother and son is necessary for the construction of their relationship. It is well known that many mothers find it hard to allow their sons to separate from them. The result is unhappy sons who have difficulty bonding with their wives and building healthy intimacy. These sons often fail in their careers as well.

Hannah fears that after she gives birth, she will bind Samuel to her. However, she understands that she must liberate him in preparation for a greater mission and for bringing the kingdom to the People of Israel. The coat that she sewed is the epitome and the highest and noblest expression of this liberation. While sewing it, she also frees herself from maternal possessiveness. She sewed a kingdom for her son, since it is Samuel who will enthrone King David and build a kingdom in Israel.

On Rosh Hashanah, we must liberate ourselves in order to connect to the work of God and the work of prayer. We must build a kingdom for ourselves. We must be kings and queens so that we can enthrone ourselves and become part of the great kingdom. This is a long and complex transformative process. It is a special synergy that forms between man who was created in God’s image and God, King of Kings. Reading the haftarah about the story of Hannah who sewed a kingdom helps us understand the concept of mission and kingdom, which is the main mitzvah of Rosh Hashanah in its deep spiritual meaning.

On Rosh Hashanah, the shofar is sounded in three different ways: Malkuyot (kingdoms), Zichronot (memories), and Shofarot. Kingdoms are not received, they are structured. By means of the coat, Hannah structured Samuel’s process of preparation and maturation for receiving the kingdom. Today, on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the whole world is amazed by how 21st-century England continues to build the mental concept of royalty not only as a symbolic entity but as a real entity with the external physical trappings of royal attire, a cloak and a crown.

The world needs kings, coronations and kingdoms. Our collective farewell to Queen Elizabeth II and the coronation of her son King Charles III is a conscious process of building kingdoms in the profound spiritual sense of the word, which is part of today’s Rosh Hashanah mitzvot – building the kingdom of God. This is the building of a kingdom within the context of democracy and freedom of choice. The citizens of England pay taxes to continue to preserve the monarchy because they need it and the world, which cooperates with what is going on in the palace, also needs it.

When we read the haftara on the first day of Rosh Hashanah, we remember that we all need a spiritual mythological mother, an artistic poet like Samuel’s mother Hannah, who will sew us a coat of vision and royalty and show us our path and our mission in this world towards emancipation and royalty, and will be a source of strength and inspiration for us to worship God out of love. May we all have a wonderful year, a year in which we fulfill our mission to create a better world replete with love and giving. With the blowing of Malkuyot (kingdoms) on the shofar, may we succeed in building a better world with a common cosmic good of baseless love, justice and peace.